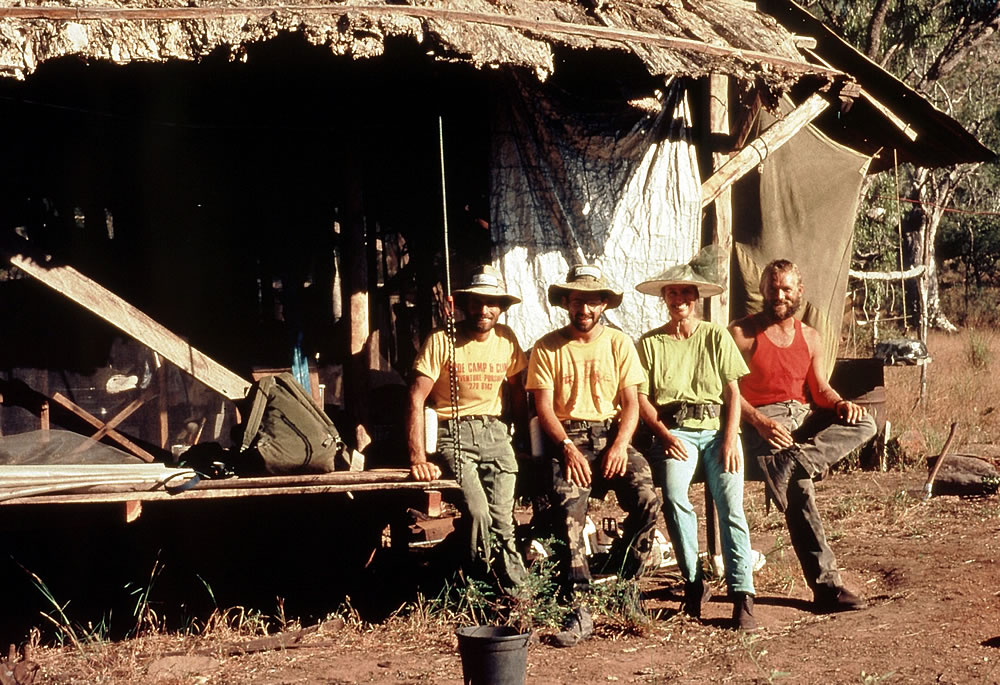

Around the Kimberley Expedition 1988

Terry Bolland & Ewen MacGregor

Support: Dennis Sproul & Duncan Hepburn

On June 8th, with 200kms of our 700km paddle behind us, Ewen and I toiled against large relentless waves, south-east of Koolan Island. It was a pleasure to be close to an island after being rammed by a shark and battling the elements for 3 ½ hours. Exhausted, we paddled in silence along the rocky shoreline slowly creeping towards a semi-circular pebbly beach both eager to step ashore to have lunch and rest.

Suddenly with no warning there was an enormous splash close to Ewen’s kayak. I glanced over and was confronted by the most chilling sight. The open jaws of a crocodile were gripping the stern of his kayak. “Croc paddle fast”, I bellowed. Ewen let out a shout of terror and accelerated.

The croc released its grip but the respite was short lived, seconds later it exploded from the water and struck again, its open jaws bent on crushing the kayak. My rifle was strapped on the back deck in a watertight case so it was of no use and if I turned around in the cockpit, my unstable craft would capsize, then I would be in deep trouble.

It was terrifying and I was helpless to assist my friend. The predator’s jaws were locked around his kayak’s stern. It lifted its head high out of the water and, with a tilt, tried desperately to put the kayak into a death roll. Looking at this horrific sight fear was shaking my body, I was icy cold, and my heart raced out of control. My mind tried to refute what my eyes were seeing, but this was no Jaws movie or Crocodile Dundee, it was real.

Ewen never looked back to glimpse his predator but he felt its strength. His arms pumped like windmills and his kayak, although heavily laden, ran swiftly through the water. The croc lost its grip again and disappeared under the murky water. Several frightening seconds ticked by. When or where would it attack next?

I now had to pass the area where the croc had submerged so I was now concerned for my safety and in my mind urged Ewen to come back as it was his croc.

By now Ewen was several metres in front of me and as I sliced past the crocs foaming waters, I paddled hard to reach the waves breaking over the sandbar ahead. I continually scanned the water behind expecting the croc to attack again. Minutes seemed like hours. I still had the thoughts, would the croc attack me next?

After paddling 2 kilometres out into the open sea, Ewen finally allowed me to catch up with him. He was badly shaken so I tried to turn our frightening experience into a light hearted joke as we still had 3 weeks and 500 kilometres to paddle and we had no option but to keep going!

I have spent over 200 days canoeing in these dangerous waters and I have been chased by crocs on several occasions, but this was the first time that one had actually attacked. It was only last year in 1987 that Ken Cornish and I had been at the head of the Prince Regent River when a tourist, Ginger Meadow who was on a tourist boat was taken by a croc, and this year it was nearly our turn! She was swimming to a boat from a waterfall at the time.

In the far distance our destination shimmered in the heat haze. Walcot Inlet, the home of the giant whirlpools was four hours away and with the previous stresses of the day it was going to be a hard paddle. As we approached the inlet we encountered driftwood, carried by the rising tide, which was hard to distinguish from crocodiles. Our campsite lay ahead. I pointed to a boulder strewn beach partially hidden from view by extensive mangroves.

We suddenly focused on a mangrove bough that jerked into the water ahead of us. “Oh no, we’re not going to camp here”, Ewen shouted. It looks too much like croc country. Looking west towards the sun disappearing behind Fletcher Island, I said, “it’s too late, there is no other campsite nearby”. With 150 metres to go, we raced through the gap in the mangroves and struck the boulders and quickly jumped out. Convinced a big saltie was in the area, I gingerly waded into the murky water, unstrapped my rifle and we took it in turns to stand shotgun as we unloaded the kayaks.

********************************

After four expeditions in the Kimberley I was determined to plan another, bigger, better and harder expedition. My plan was to go around the Kimberley, starting and finishing at Broome, keeping to the most isolated regions and using four different disciplines:

Running 445km

Kayaking 700kms

Backpacking 420kms

Mountain Biking 1930kms

The most important objectives of the expedition were firstly to explore the areas around the Mitchell, Hunter and Roe Rivers and secondly to retrace the movements and find material evidence of the two German aviators, Bertram and Klausmann, who became stranded along the Kimberley coast in 1932.

We aimed to push ourselves to the limit, to have minimum rest days and achieve high milage over a three month period. Dreaming up such an expedition was easy. Finding the money and companions willing to put themselves under severe pressure for three months was much harder.

Eventually I convinced an experienced white water kayaker Ewen MacGregor, who had recently migrated from the UK that it would be a trip of a lifetime! Two of Ewen’s friends, Duncan Hepburn and Dennis Sproul, also from the UK agreed to be our support team. Ewen, Duncan and Dennis had no idea where the Kimberley was and what to expect. For my part, being an Adventure Pursuits Instructor and having already completed four previous Kimberley expeditions, I was the only one who had some insight into what lay ahead of us.

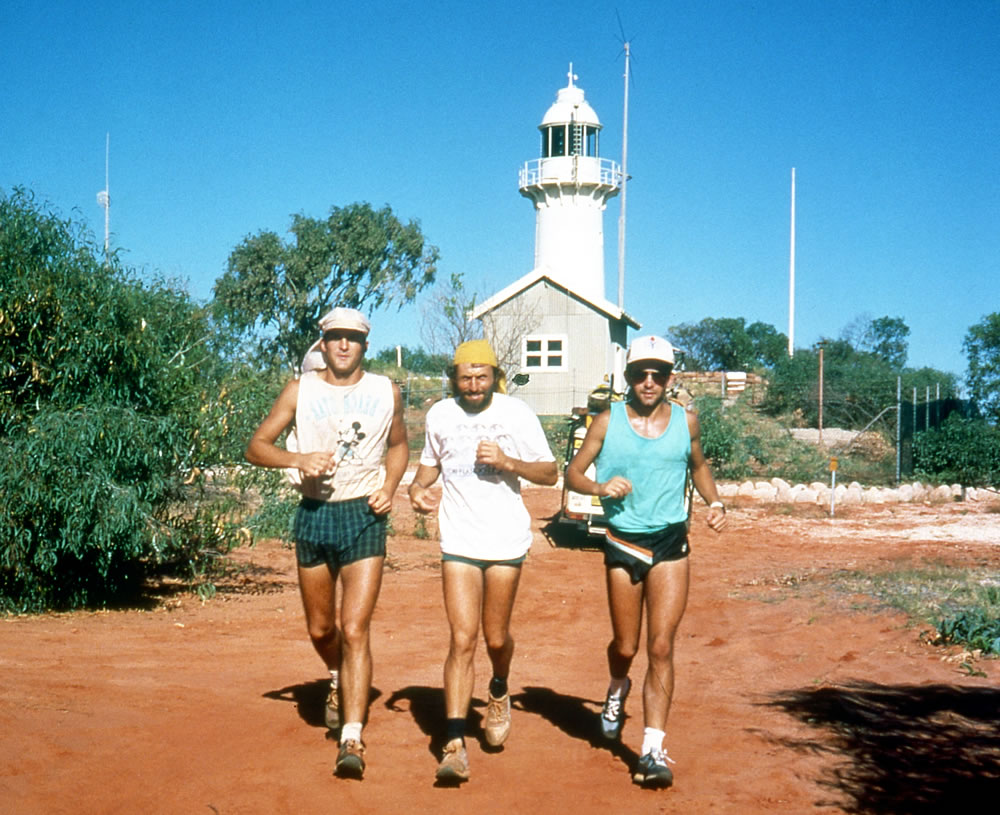

At 7.30am on 25th May 1988 in Broome, Ewen and I warmed up for a 225 kilometre run and the beginning of a gruelling 3500km challenge across rugged and unrelenting, yet magnificent, Kimberley terrain. Broome was still quiet. There was no fanfare for our departure, only Duncan and Dennis witnessed the start of our daunting marathon.

By 1.30pm and in 36 degree heat, Ewen and I had run 35 kilometres along a dusty corrugated track. At our refreshment stop we were hot, exhausted and we both sat in silence. Ewen’s pace had slowed to a stagger and by the look on his face he could collapse at any time.

I broke the silence. How do you feel, I asked.

I’m feeling dizzy and just feel like dying, he muttered.

This was the first day of our gruelling journey. As Ewen fell victim to the extreme heat and conditions, Dennis kept me company, running the next 40 kilometres. When it became dark it was extremely hard to run on the ruts, the corrugations and the sand patches, so we walked. The moon helped enormously as it gave us just enough light to see our feet and get our fatigued muscles to our first nights camp. The highlight of the day was when a lady Moya Smith stopped to talk to us. I had met Moya in 1982 on my first trip. At the time Moya was learning the old traditional ways of hunting and fishing from the Aboriginals and I stayed with them for 10 days trying to learn as much as I could. The elder Aboriginals Sandy and his wife who taught Moya and myself the traditional ways were in the car with her.

A thick mist in the night had dampened all our gear and when we took to the road it was like running through a tunnel of mist. When the mist disappeared with the sun the mysterious morning vanished and the birds started singing. At the 40km mark Ewen felt the full force of the scorching sun and decided to retire again. When we got close to Beagle Bay the boys drove into the community to have a look at the church with a pearl shell alter whilst I ran on. Soon after the turn off the road deteriorated even more making the running even tougher than it was. To make matters worse we didn’t have ice or cold water so it was harder to quench my first. It had been another really hot, tough day and by 8.00pm, when it was cooler and dark I had run 80kms.

My third day on the track I only had to run 65kms but I knew it was still going to be a tough day. With the birds singing and some cattle roaming we slowly entered the heat zone and by the end of the day when the sun was setting over the quivering blue Indian ocean we arrived at the Cape Leveque lighthouse. With 225 kilometres behind us, our dream of resting under the palm trees of Cape Leveque was very welcome.

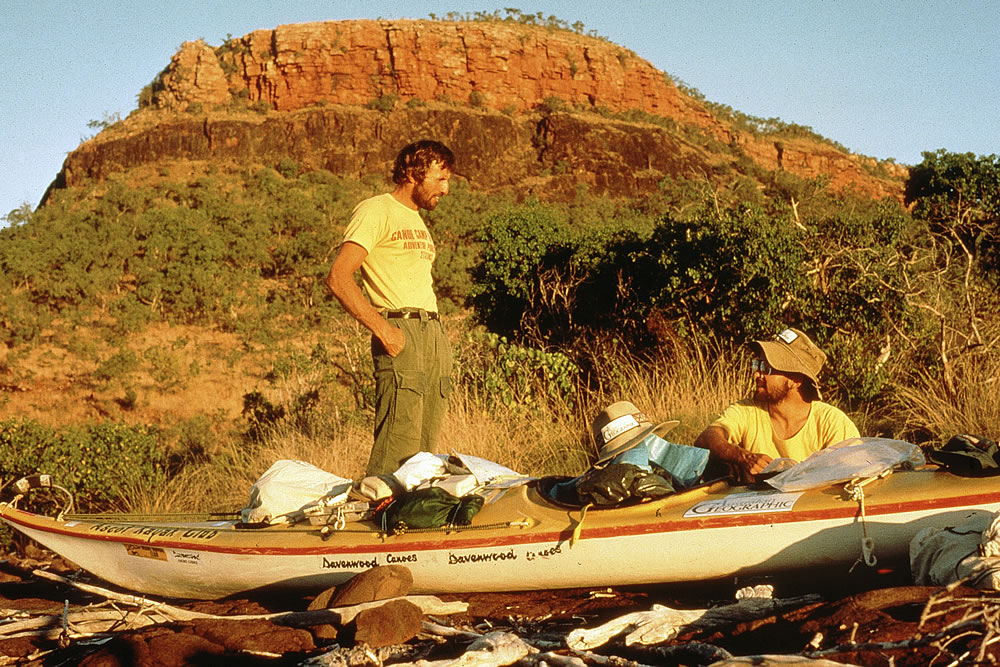

No time was lost before Ewen and I commenced our 700 kilometre ocean paddle along one of the worlds most treacherous coastlines. Tides in the King Sound are among the highest in the world, exceeding 10 metres with two high and low tides per day. Swift currents reach speeds of 12 knots in many places. The coastline is isolated and crawling with sharks and crocodiles. It was truly a wild, wondrous coastline.

Our kayaks were loaded, mine on the left having a bit more weight to carry

To reach East Sunday Island, our first camp site, we had to paddle across several swift currents between the islands. It was a good introduction to the Kimberley but being experienced white water paddlers we took the strong currents in our stride but admittedly the crossing that we had to ferry glide across were must bigger than river ferry glides. We settled in at our campsite and planned the following days paddle. The tides were on springs which meant they were at the highest and fastest of the month so the 15km crossing was going to be a challenge.

I awoke to a howling wind from the north-east and drifted in and out of slumber for the next few hours. Signs were not favourable – giant tides, fast currents and now a gale. As we rose a red glow emerged behind Mermaid Island and finally the sun appeared to reveal massive white caps that dominated the huge expanse of water of King Sound. Swift tidal currents forged past our reef and the rocky island beyond.

Anxiety cramped my stomach. Conditions were far from ideal for such a treacherous crossing. For the next hour we carried our gear down the beach in silence, lost in our own thoughts. The tedious job of loading the kayaks was completed some distance from the water’s edge as the tide was rising at an alarming rate.

Every piece of equipment had its place and failure to load it correctly would mean unloading and starting again and we had little time today to do that. The silence between us continued until we were both satisfied with our preparation and ready to leave the safety of the shoreline.

The kayaks sat deep in the water, fully loaded with 140 kilograms of camping gear, food packs, fresh water, radio, battery and solar panel. We wore buoyancy aids and survival jackets jammed with emergency equipment, including a distress beacon, flares, mask and snorkel, signalling mirror, fishing, fishing line, matches, compass, spare food and 700mls of water. Separated from our kayaks we hoped to be self-sufficient for a few days, although water would be our biggest concern.

As we rounded the lee of the island, the wind and currents created a mass of towering waves which pounded us from all directions. The ride was wild and far more difficult than handling river rapids with its safe banks on either side. A big wave hit our boats and Ewen said that he nearly went over. The further we moved from the island the calmer the ocean became, although it still wasn’t an easy ride. We could have waited a week for the neap tide, when they create less current but it was much more exciting to cross the sound on spring tides and a much faster currents.

Mermaid Island, our destination 15kms away was lost in the haze, but as we closed on the beckoning golden beach, the swift currents swept us south-ward deeper into the open waters of the King Sound. Realising that it was an impossible task to reach Mermaid Island, we focussed our effort on Long Island which was several kilometres to the south. Failure to reach there would mean spending the night out in the open ocean drifting with the currents towards Derby, so after a short water stop we paddled as strong as we could and our efforts were eventually rewarded, although we missed Long Island and landed on Fairway Island just west of Long. This was the last small island that we could land on before being swept into the massive open ocean of the King Sound so it was a relief to have landed. We climbed the highest hill to check out the tide and saw the swift currents fly by the island at a rapid pace. It was a sight to see. When the currents eased we jumped back in our kayaks and paddled across to Long Island to camp.

We camped at Hells Gate where the currents are just unbelievable

As the days passed we appreciated the beauty of the magnificent coastline which was indented with hundreds of bays and islands. The high cliffs, rich in colours and a variety of peculiar patterns dominated the unpredictable ocean, riddled with treacherous reefs where fish leaped in silver cascades and turtles floated peacefully in the habitat of the lurking salt water crocodiles.The grandeur of the surroundings certainly eclipsed the pain of paddling and the anxiety caused by the sharks hits, crocodiles and the foaming rapids we had to negotiate.

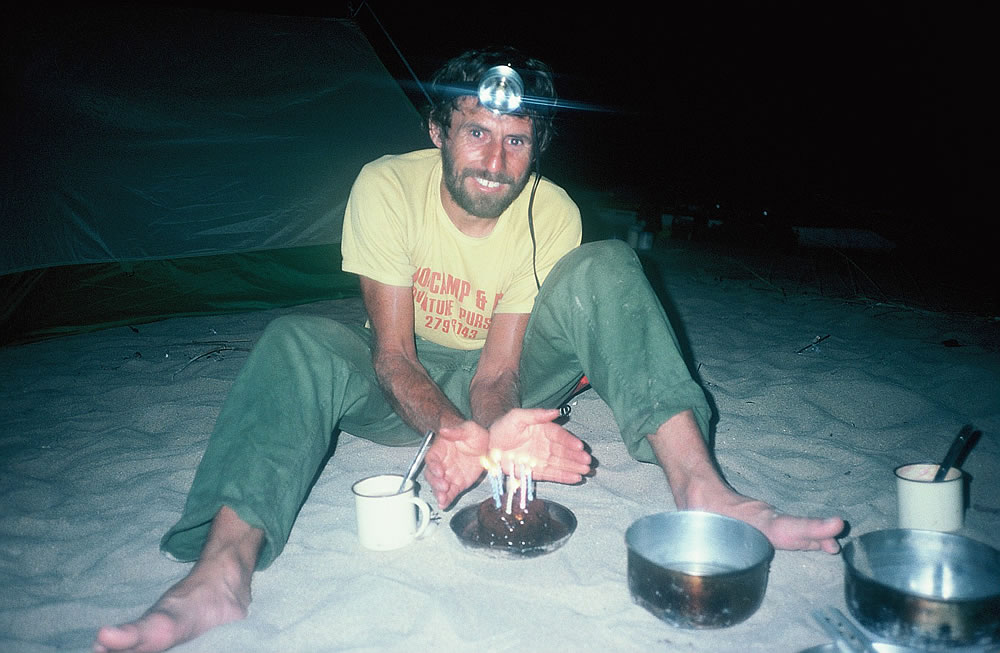

On June the 3rd intensely folded rock formations dominated our camp site and my birthday beach. Ewen a chef by trade, fished under a spectacular red patchy sky oblivious to the lurking crocs that could be watching him. In the dying light he hooked a small shark, which he cooked in garlic. Plum pudding in a rich sauce with glowing candles followed, providing a wilderness birthday meal I will never forget.

A beach between Cockatoo and Koolan Islands. My birthday

Ewen cooked me a great birthday meal, finished off with a small birthday cake

Ewen cooked me a great birthday meal, finished off with a small birthday cake

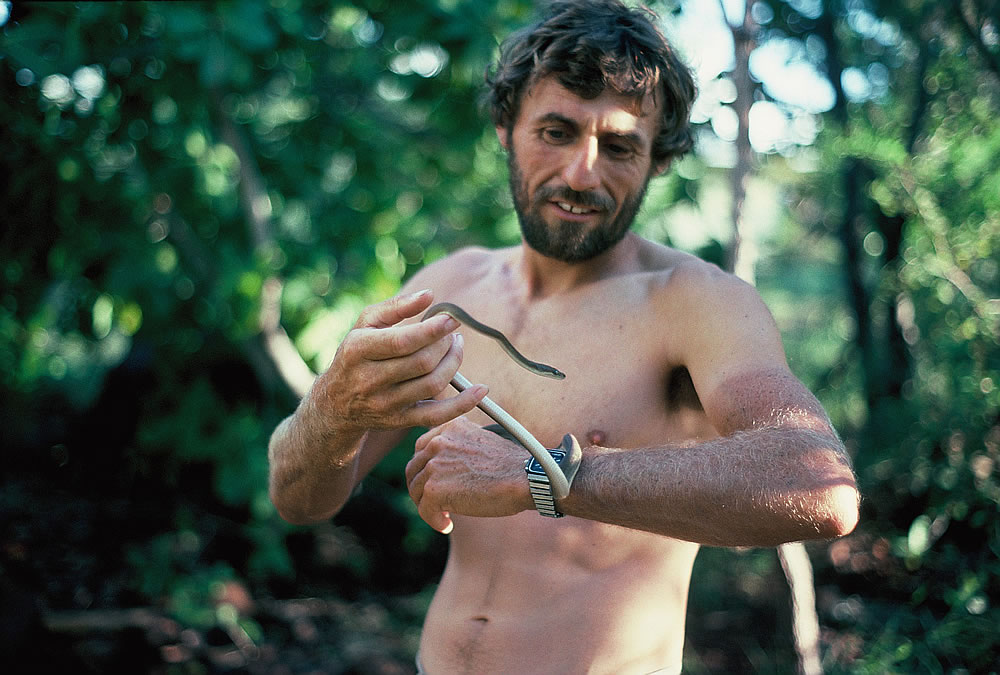

At Koolan Island we visited our friends Lee Vernon and Norm Lindus who were holding our food packs. I first met Norm in 1983 at King George River on my second Kimberley trip. He was helping an old friend of mine Mike and his family to sail a yacht to Darwin. Then on my 1987 after stopping on Koolan Island, Lee who was a keen naturalist, invited Ken and I to drop in for dinner. When we arrived, Norm who I only met briefly 4 years earlier, greeted me at the door with a python wrapped around his neck. We were both surprised, when in conversation we realised we had met before. Since then we had kept in contact.

Their home, overlooking the ocean was a haven for injured birds and animals. Two yellow throated minor birds and Dave the dove were three of their regular visitors which flew into their home through open shutters. They were also educating the community about snakes. Preserving the animals and environment was an important part of their lives. The morning we left an olive python had made his home in one of the bird baths.

As we said goodbye to lee and Norm with kayaks jammed packed with gear, they insisted we took a freshly baked fruit cake, which Ewen fitted between his legs because we had no other place to put it.

We pushed on, leaving a large colony of white bellied sea eagles hovering and made camp further along the coast opposite the Traverse Islands. Ewen hadn’t taken the opportunity of washing in the light, and mosquitoes savaged him as he walked around in his shorts. After dark he strolled down to the beach to wash. The water was lapping gently into our cove. Nothing could be seen in the dark shadows of the ocean, so it was out of sight out of mind.

When he returned to camp I politely warned him again about the dangers and crocs and to always wash away from the water, especially at night. We had only been canoeing for about ten days and it was Ewen’s first trip to the Kimberley. So far he hadn’t taken my warnings about the hostile environment too seriously, despite his kayak being hit by sharks twice already. Maybe the beautiful scenery and excitement of the trip was leading him into a false sense of security.

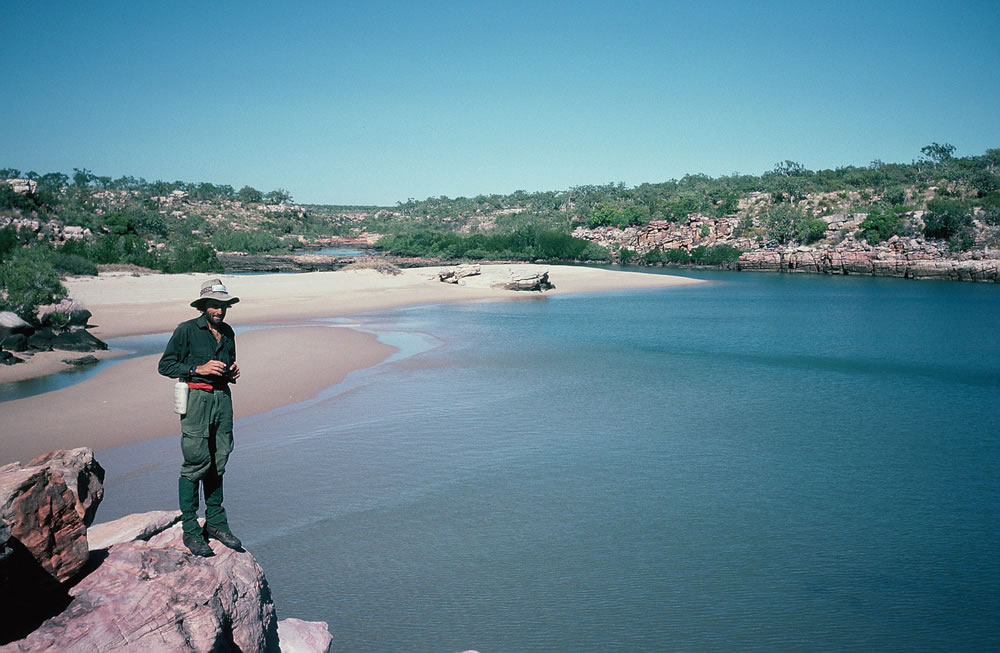

The coast heading towards Walcott Inlet

The coast heading towards Walcott Inlet

The coast heading towards Walcott Inlet

Small things, like infected sandfly or mosquito bites can turn into a major problem. I emphasised, taking precautions, just being in a kayak in the daylight is a risk, washing at night is suicide.

As Ewen listened to the old man giving him advice, a rocket flare near Koolan Island lit up the sky. Somebody must be in trouble but what can we do in kayaks at night. I tried my radio but couldn’t make contact, so we had to wait for the following morning to inform the authorities about somebody possibly dying out there. Our concern was not needed as there had been a flare demonstration on Koolan Island.

My words of wisdom hit home the following morning as we passed Helipad Islands on our way to Walcott Inlet. It was here the crocodile attacked Ewen’s kayak and after that he took maximum precautions.

The current running into Walcott Inlet

Walcott Inlet

Walcott Inlet

Walcott Inlet

That night after the attack, at our campsite at Walcott Inlet, I told Ewen a story about a kayak trip down the river Nile that I had read about.

….One night a croc was attracted by some meat being stowed in the kayak and tried desperately to get it out. Unsuccessful , it returned to the water, but had left a musky scent on the boat. The following day, the kayak was attacked several times. It is believed that both sexes use the musky secretions to locate and attract each other….

After telling Ewen the story, he scrubbed around the scratches made by the crocs teeth, very thoroughly! No amorous crocodile was going to mistake his boat for a possible mate! A huge tree trunk that was bumping the cliffs and water lapping into rock crevices, echoed around the cove throughout the night. Having no time for breakfast we left the quivering mangroves and high-tailed it further north along the mangrove lined shores.

Bleary eyed from the glare, trickling sweat and stinging salt, we paddled hour after hour trying to overcome our trance like state. In a flurry of confusion Ewen yelled out and took off like a man possessed, as a shark suddenly hit his rudder. Minutes later and still shaken from the shark hit, he shouted out with fear in his voice, “I can’t take much more of this”, as he saw another shark rapidly approach, veering off only a metre from his hands.

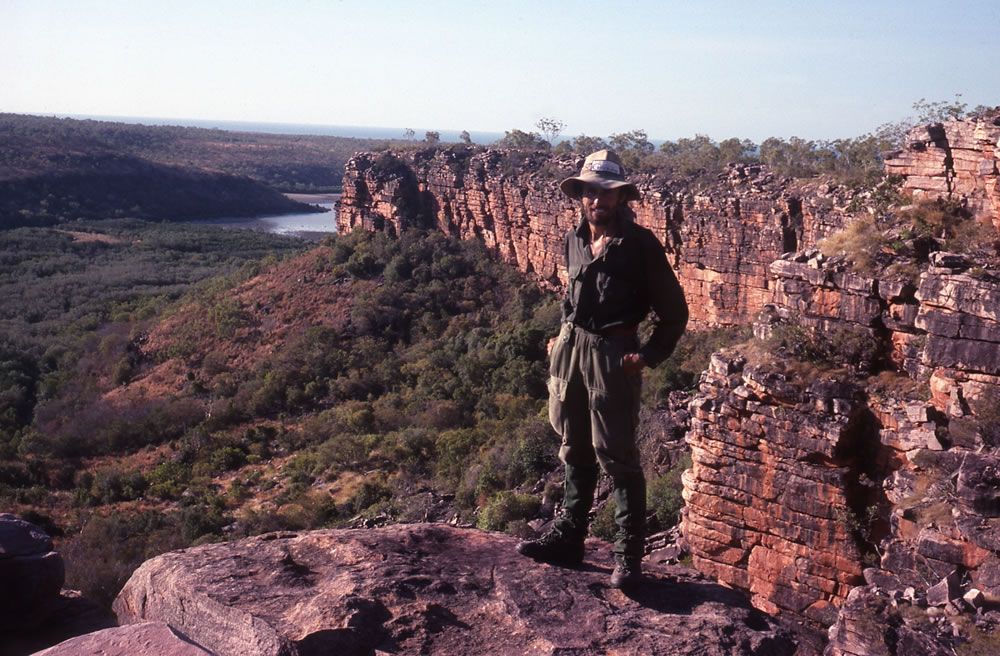

It was going to be one of those days! So to restore our energy and enthusiasm we rafted up and ate some dried fruits and headed for Raft Point. Our camp at Raft Point was just as stunning as the other 3 times I had camped there. A walk along the cliffs with the ocean on one side and the bay with mangroves and vertical cliffy islands on the other was a sight to die for.

Raft Point with Steep Island in the background

As we left Raft Point, with the tidal stream in our favour for once, we cruised at 10kph at times. After failing to find freshwater in the coastal creeks our luck changed at Freshwater Cove. Here, freshwater cascaded from the clustered tentacle root system of mangroves into a 20 metre pool, which blocked our progress. To be safe, we skirted the pool and climbed through the sprawling roots to the trickling stream. Camouflaged in the pool below us, a saltwater crocodile laid perfectly still. You can imagine how pleased we were that we hadn’t waded into the pool.

A fresh water stream spilling through the mangroves

The pearling settlement of Kuri Bay was nestled at the bottom of a cove surrounded by spectacular cliffs. Boats and pearling pontoons were scattered around the cove and sleepy settlement, fronted by a thin line of mangroves, looked abandoned as we paddled across the glassy turquoise water towards it. Eagles soared on silent wings and it was only the crows raiding the rubbish tip that disturbed the tranquil setting.

Kuri Bay gave us the opportunity to wash our clothes, repair our gear and collect rations for the final stage of our sea journey. The hospitality and co-operation of Bob Haddock and the Kuri Bay people was over-whelming, as always.

We moved on 25 kilometres towards the site of the old Kunmunya Mission where Michael and Susan Cusack, who were sponsored by Australian Geographic were living in the wilderness for a year. They only had two weeks of their year long stay to go when we reached their makeshift home by kayak and on foot. The area was plagued by flies, I believe because of the many wild mules and cattle that roamed the region. It was great to meet Mike and Sue and hear all their stories. We had so much in common and our short stay was exciting.

Before leaving Mick and Sue and a few million pet flies, we loaded our kayaks with one hundred litres of freshwater. Mitchell Plateau was 317 kms away, a minimum of ten days paddling and with no reliable water supplies en route we had to carry sufficient for entire journey.

We slept on the beaches but we were wary of crocodiles so we usually placed our kayaks in front of the tent

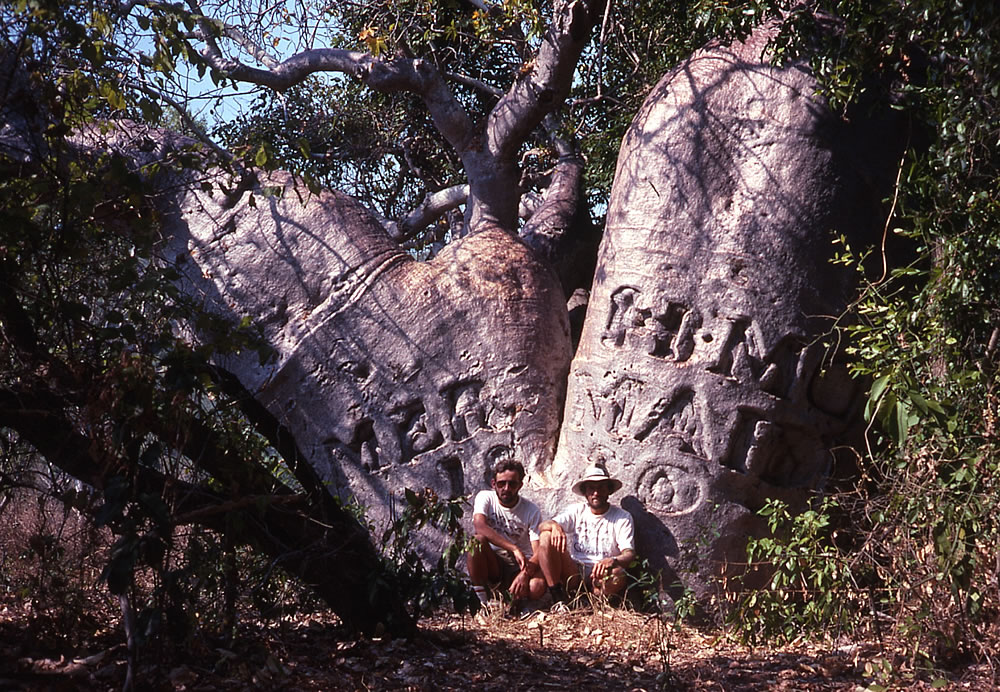

At Careening Bay, just beyond the Prince Regent River we stopped at a large boab tree in which Captain King’s crew had carved the ships name, ‘Mermaid 1820’. When we landed Ewen didn’t pull his kayak far enough up the beach and as the tide rose it started drifting away with the wind. A quick dash into the water caught it before it went sailing away. A bush fire was creating a smoke haze over the bay and when the sun went down there was an amazing glow in the sky.

Kings Boab tree (Engraved HMC Mermaid 1820)

Smoke and the sunset create a beautiful sky. Ewen near the boab tree

We weren’t to know that gale warnings had been issued for this part of the coast as we paddled for up to 11 hours a day, battling our way towards Mitchell Plateau. The howling wind and constant saturation from the waves caused a massive heat loss from our bodies and we were often cold which was hard to believe in such a hot environment. Only days before, the stifling heat had been unbearable.

We often paddled before sunrise

We often paddled before sunrise

We had to be careful not to drink too much water in the morning, because it was a difficult task trying to urinate in a container in the rough seas. It was a harsh and hostile environment, the coastal ranges were barren, the sea was rough, the tides were swift and crocodiles, sharks and sea snakes were our constant companions. The nearest civilisation was hundreds of kilometres away.

On June 27th 1988 we cruised into Crystal Creek in Admiralty Gulf to find the falling tide had left our only access, a narrow channel which cut through a mangrove swamp, and the home we had been told of two saltwater crocs, a muddy, slippery mass of oyster laden rocks and steep muddy banks . It looked an evil place and as our memories lingered back to croc attack nearly 3 weeks previously, we shunted nervously towards a barrage of muddy boulders ladened with razor sharp oysters. Stranded by the low tide, we faced a three hour struggle to hoist our gear to the top of the cliff, to where eventually Dennis and Duncan greeted us with champagne to celebrate our safe arrival.

The tide left us high and dry. The slippery oyster laden rocks made it very difficult for us to unload

Our celebrations were short however, for the following day all the canoeing equipment had to be cleaned and packed away and our walking gear and rations prepared. Mike and Susan Cusak kept in regular contact on the Flying Doctor radio and that evening we talked to Dick Smith who had helped us with $500.00 sponsorship. Dick had been to Mitchell Falls by helicopter the previous day.

Duncan and Dennis had been living it up in Broome while we were paddling and they had won $100.00 worth of booze which they had used to entertain the ladies. They had driven north through rough terrain to meet us at Crystal Creek and they would soon share the stresses and strains of our first walk. But first I had to complete a 65km cycle ride through at times 8 foot high grass, gulley crossings, steep jump ups and boulder strewn tracks to Mitchell Falls.

Water was cascading over its four drops into deep pools. The beauty never fails to impress me. Along the gorge the orange sandstone cliffs tower towards the sky, their rugged walls reflecting in the large pools below.

Shaded by paperbark trees, the pools had banks laden with wild passionfruit and were home to many Johnson crocodiles and water monitors. From the top of Merton Falls, 200 metres north, we gazed at two freshwater crocs basking under a rainbow thrown by the cascade.

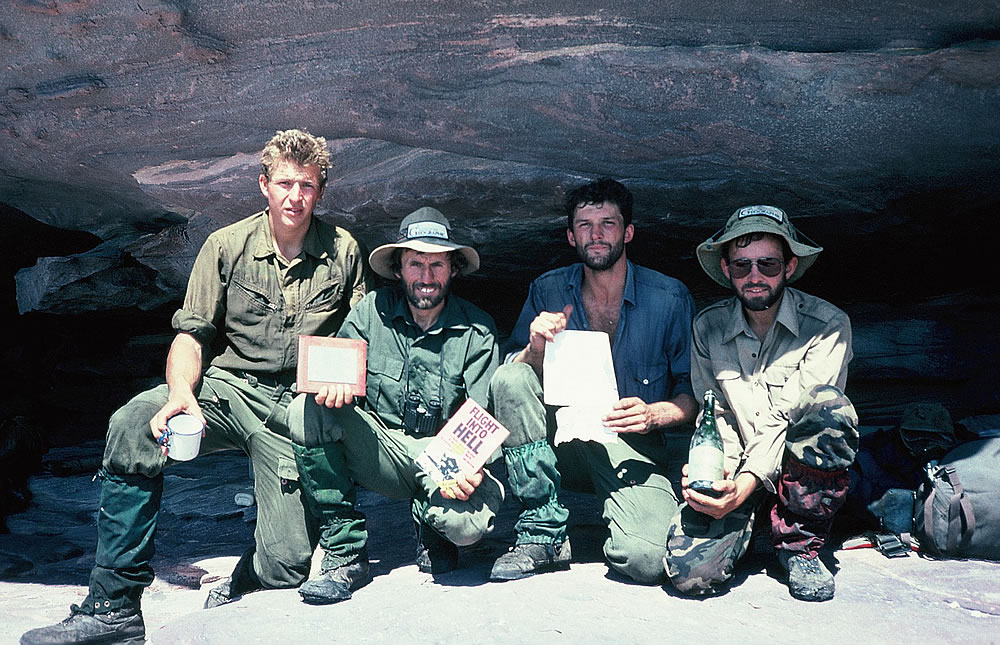

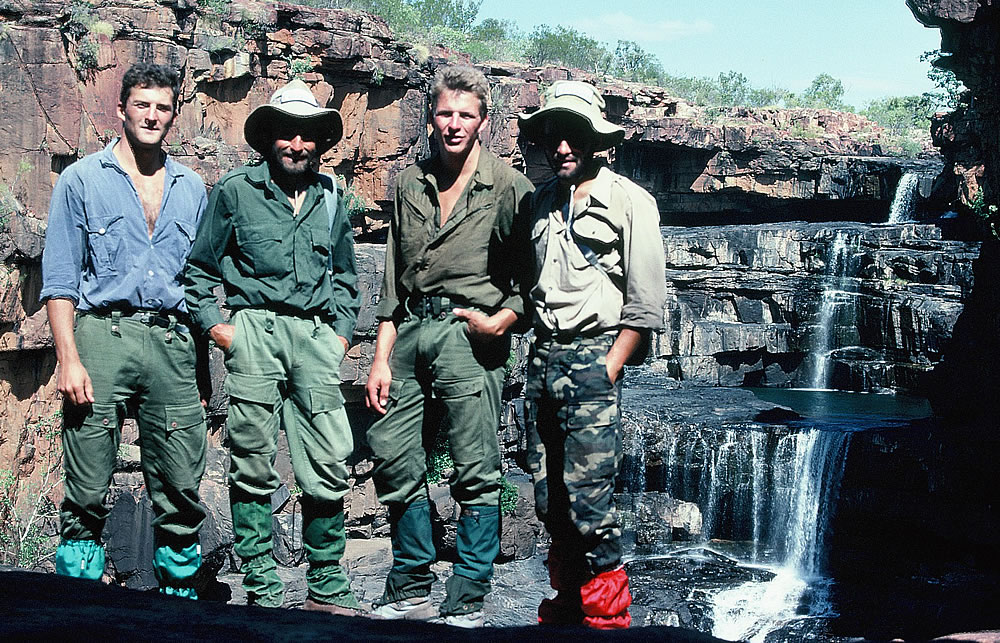

Mitchell Falls. Dennis, Me, Duncan & Ewen

Mitchell Falls. Dennis, Me, Duncan & Ewen

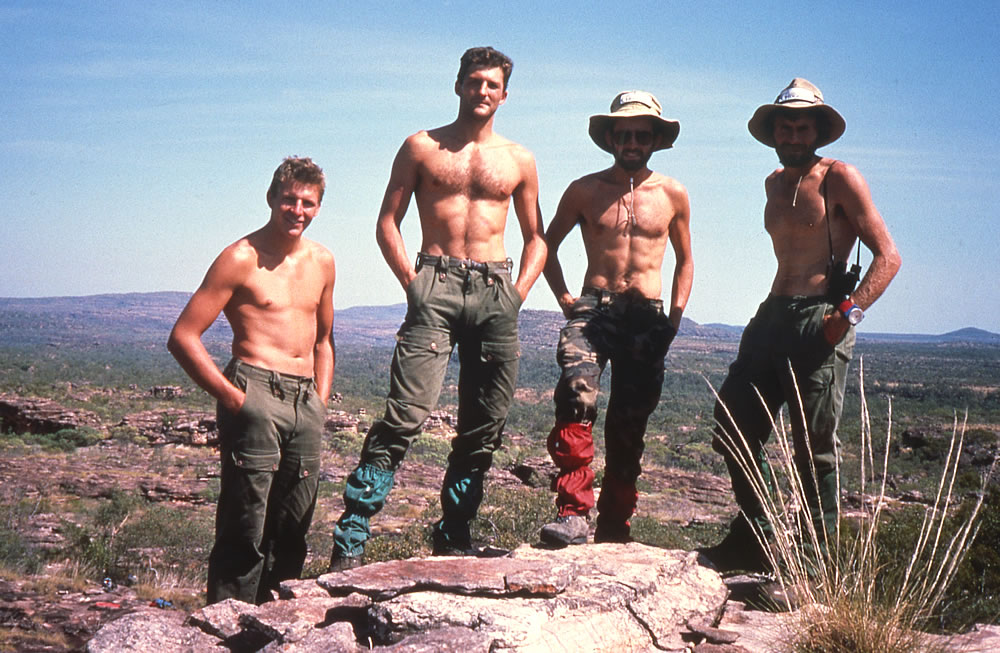

At the falls car park Ewen, Duncan, Dennis and I prepared for a 20 day walk across to Hunter and Roe Rivers. We carried only 12 food packs as we would go on half rations. As we headed towards an unnamed waterfall on the Hunter River we were forced to criss-cross many ravines, climb sandstone outcrops and fight our way through stabbing chest deep spinifex that oozed sticky resin on our clothes. It was a back packers nightmare and as the shadows grew longer, Dennis and Duncan descended a rock face into a carpet of spinifex below. Ewen, exhausted and still recovering from an oyster slash on his toe, tripped on a vine and fell head first down a two metre drop. Pinned under his pack we feared the worst. Luckily for Ewen his fairy Godmother watched over him, he stumbled off into the sunset with a cut thick lip and a bruised hand!

The walking was difficult much of the time. Ewen & Dennis

Reaching the base of the 415 metre Donkers Hill the sweat poured off our bodies like tiny waterfalls. As an array of coloured butterflies and swallows criss-crossed the sky above the conical summit, we enjoyed a well-earned rest and looked out towards the 484 metre Mount Anderdon and the distant waters of Prince Frederick Harbour. To the south and our route to the Roe River, a raging bushfire loomed on the horizon. Descending Donkers Hill to the cliffs flanking Hunter River we discovered a small pool. Within minutes Dennis had thrown a line into the water and hooked a fish with a raison and then hooked another one with no bait at all. We had a good feed that night. The area was rich in birdlife including the black grass wren, the shining flycatcher and the rare white-breasted robin. That night like several other nights a quoll (native cat) shared our campsite and fish leftovers.

Nearly at the top of Donkins Hill with the Hunter River in the distance

Nearly at the top of Donkins Hill with the Hunter River in the distance

Duncan and Ewen on Donkins Hill

The top end of Hunter River where the tide just reaches

As we trekked towards Roe River the orange glow of the bush fire lit up the night sky. The fire was split into several pockets and as walked through the charred areas it felt like a war had taken place, as no blade of grass or tree escaped the scorching inferno. As many tree stumps continued to blaze, several trees crashed to the ground and in areas not yet burnt, flames leapt 20 metres into the air.

At times we could only achieve 1km an hour while walking. It was tough but we reached the Roe River gorge. Leaving the impressive Hunter and Roe River gorges behind, we returned to the Mitchell Falls to meet our new friends Mike and Susan Cusack who were going to lend Ewen a mountain bike to use for the rest of the trip as he didn’t have a bike.

With our arduous thirteen day walk finished Ewen and I jumped on our mountain bikes and cycled 450kms over deteriorated tracks towards the King George Falls, detouring 50 kilometres to buy an ice cream at Kalumburu Mission. The track leading into King George Falls is used rarely used so for 200 kilometres we bounced over boulders, dodged rocks and sank pedal deep into soft sand. Small trees growing in the middle of the track were fortresses for green ants. To disturb them was fatal as their nippers sank deeply into our flesh. Sweet revenge was to brush them off further along the track and give them a long walk home.

Children at the Kalumburu Mission

Children at the Kalumburu Mission

At the top of King George Falls

With Ewen nursing a buckled wheel due to a branch in his spokes, we arrived at King George Falls. The dry season denied us the beauty of a huge amount of water from tumbling majestically into the glistening saltwater river below. Massive 80 metre vertical sandstone cliffs extended 12 kilometres to the Timor Sea. In the distance a few wisps of smoke from a recent bushfire hovered in the cloudless sky. It was a stunning scene.

Our objective now was to retrace the steps of one of the great survival epics of Australian history. In 1932, two German aviators, Hans Bertram and Adolf Klausmann, force landed their seaplane, Atlantis, on a remote part of the Kimberley coast.

With no fuel to go on, the two men were at the beginning of what was to become a remarkable fifty-three day struggle to survive in a hostile environment, a struggle which was to bring them to the brink of madness and death.

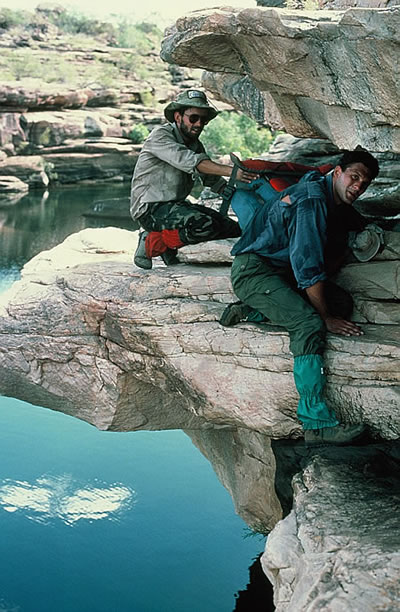

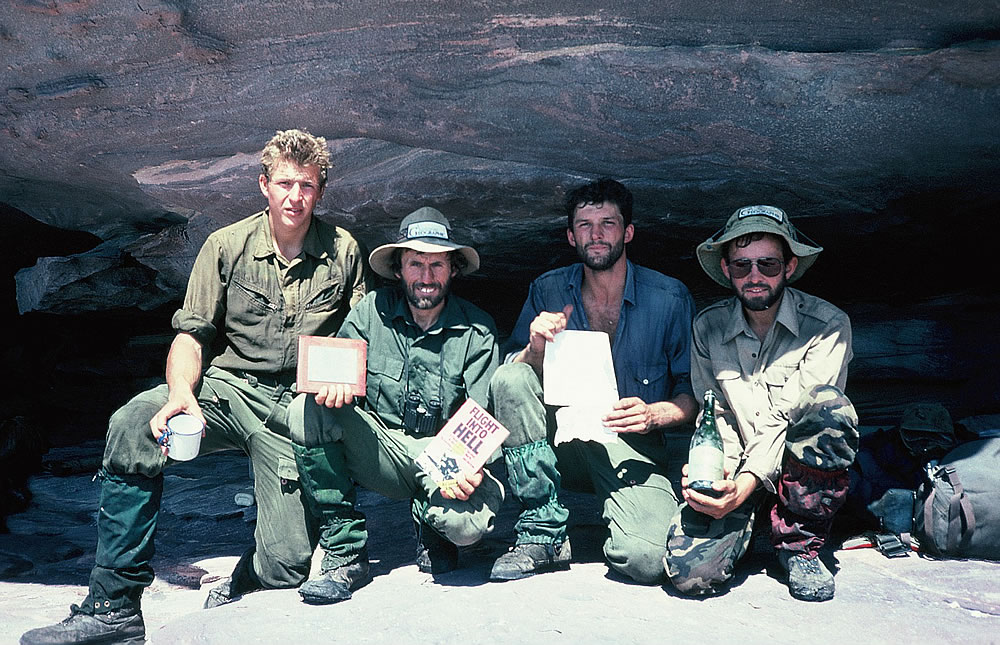

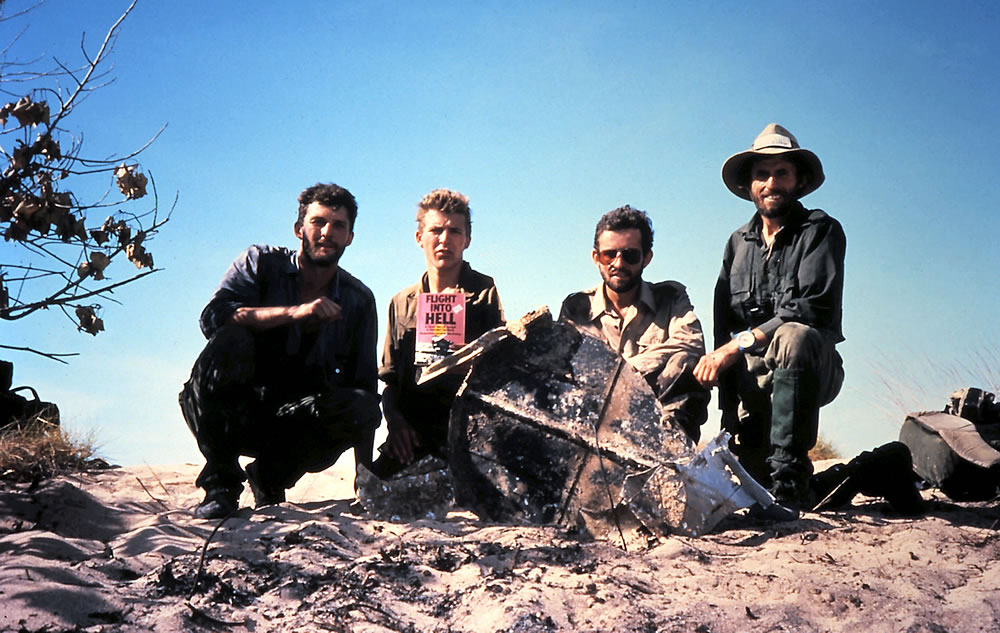

Armed with a copy of Bertram’s book, ‘Flight into Hell’ we walked overland to find the cave at Cape Bernier. The cave is where the aviators spent their final days before being rescued by an Aboriginal search party.

The cave that Bertram and Klausmann took refuge in

It was on July 19th, 1988 when we found the cave, well it was more of a big rock overhang. We were quite proud to be sitting in the same cave that Bertram and Klausmann had done all those years before. Now we wanted to find the place where they had come ashore in the float they used as a canoe so we continued west along the coast for about 2 ½ kms. Our perseverance paid off, Ewen noticed a tint of aluminium smothered by sand close to a bush. Incredibly it turned out to be part of the bulkhead from the damaged float that the survivors used as a canoe in one of their attempts to paddle to civilisation. We were ecstatic. The chances of finding something after 56 years seemed impossible. The area matched the description in Bertram’s book, including the lifesaving waterhole beyond the adjacent ridge. A small cairn had been built higher up the beach. Had Bertram built it?

We found part of the seaplane float after 56 years being under the sand

After retracing one of their inland walks back to the King George Falls we loaded our find in the Toyota and Duncan left for Wyndham, leaving Dennis, Ewen and I to trek 240kms across a vast Kimberley wilderness. Whatever happened now, our nearest remote outstation was 200 kilometres away.

Our journey to Forrest River, via Emergency Bay, the Atlantis’s forced landing sight, became a nightmare. We were walking through tick infested scrub and dry creek beds which turned into a hellish trip. Tormented by the heat, the flies and heavy backpacks, which included 7 litres of fresh water, there seemed little hope in finding fresh water on our way. By days end though, relief was in sight, when we found a pool of water but soon after our hopes were dashed when it had been fouled by cattle dung and urine. We camped beside the pool and as we didn’t know where the next water hole would be we filtered the putrid water through Dennis’ hat (which never smelled the same again), before boiling it. The water tasted awful and although we mixed a little with our cooking we were hoping that we wouldn’t have to drink it before finding purer water.

As we set off the following day our water concern was highlighted as we crossed more dry creek beds and parched landscape. Our sombre mood suddenly changed to sheer joy when we entered a lush valley with pandanas palms, green creepers and tall grasses bordering a beautiful sweet running stream. It was like leaving hell and entering paradise, where birds probed the flowers of silky grevilleas, where sweet running water cascaded over shiny rocks and into small clear pools. Downstream closer to the ocean rugged cliffs grew higher and higher.

The cliff line leading into Emergency Bay

Our polluted water supply was tipped from our bottles and replaced with the clean pure water. Our joy of finding such a place, when you have thoughts of drinking cattle urine for several days was a feeling that you could never forget.

Reaching Emergency Bay the rocky shoreline extended 3 kilometres inland, giving way to a small beach and forest of thick mangroves. We descended the slippery shaly cliff face to the thick impenetrable mangroves that barred our access to the stream. As we stalked through the mangroves, Dennis, wary of crocodiles, held the rifle poised for the slightest movement. Like suction pads our boots grew heavy crossing the repulsive mud that supported popping crustaceans and fleeing mud skippers. With packs catching on branches and feet like lead, our chances of out-running a croc were slim.

While searching among the mangroves and rocky water course, our sweet running stream we had seen earlier had soaked underground, and like many other streams in the Kimberley was dry where it met the ocean. We now could understand why the German aviators thought that there was no water in the area, but if they had done a short walk upstream they would have found a rock pool that would have given them all the water they needed.

An investigation of the small beach in Emergency Bay uncovered fragments of decaying metal and the landscape duplicated old photographs from the books we had brought with us. From Emergency Bay we retraced the aviators first inland walk along the coast to Crocodile Creek 16 kilometres east. It was here that Bertram wrote in his book: Crocodile! Two-three, swimming towards us. For a second I am paralysed. Then …. I shout to Klausmann. Our clothes and shoes sink out of sight. In mortal terror we begin to swim as fast as we can….

Safe from the crocs; they struggled for four days back to the plane, naked, barefoot and with no food or water. By the time they arrive back at the plane they have been without water for seven days. It was very interesting trying to piece together Bertram and Klausmanns footsteps. We’d found the cave, the life saving waterhole and the bulkhead from the damaged float. We’d retraced their inland walk towards King George River, found Emergency Bay their second landing spot and where they started their first walk and sea going journey in the planes float. Now we had followed their walk to Crocodile Creek. We ponder, we check the area and try to establish exactly the place where they would have swam the creek. Reading Bertram’s book over and over again fascinated me, I could imagine them swimming and then panic as the crocs gave chase.

In their book they don’t mention the fresh water that flowed from the lush creek, one kilometre upstream of the ocean in Emergency Bay. Their quick and rash decisions had hurried them along so they failed to find the four water spots that we had found just in from the coast along their 16 kilometre trek. Coming from Europe however, they would have been expecting the river to flow out to sea and not to seep under the ground for the last few hundred metres.

Our last objective was to walk 6 kilometres further south of Cape Whisky and view their original landing spot, but we got our own surprise crossing the first small creek, after a croc leaped into the water giving us one hell of a fright. After seeing the area of the first landing site and the beautiful gorge nearby, I could understand why the Aboriginals lived there. It was a perfect fishing spot, plenty of fresh water, numerous ledges, overhangs and rock platforms. It would have been a paradise for the Aboriginals.

After successfully retracing their entire route we trekked south skirting north of the 221 metre Mount Casuarina and followed the spectacular Berkley River much of the way. Carrying the extra weight of the radio and battery we had decided to go on half rations on both walks and supplement our diet with fish. With our water sources scarce, so were the fish.

Each nut and grain was chewed slowly to capture the flavour. Not a grain was wasted. Our high level of fitness was sustained despite our whippet lean bodies, spartan rations and extreme physical exercise.

The Berkley River looking upstream

The Berkley River looking downstream

I’ll never forget the morning we had breakfast looking south east towards Mt Casuarina. Dennis was starting to feel the effects of hunger as we had been walking for a week on half rations and had yet to find a pool big enough to catch any fish. He took his breakfast and lunch from his pack and placed them both in his mug. “Look at that,” he said. “my old man would never believe me if I told him I could fit two meals into a small mug”. “Back home, I used to eat at least three bowls of cornflakes every morning”. I must be crazy.

We usually had two breakfasts, a few grains of muesli at 5.00am and the rest at 9.00am. It was now 9.00am, not 2 minutes past 9, exactly 9.00am. When food is involved, stopping dead on time was very important especially when the portions were small.

Ewen started talking about puddings and beautiful food in general. Dennis joined in, telling us what he would be eating back home. Then he took his wallet out and showed us pictures of his family. The isolation and the lack of food was making him dream of the good times. Only 3 weeks earlier, when the expedition had started he had no idea he would be trekking across the Kimberley wilderness and be 200 kilometres from the nearest civilisation, but he loved it. He was a great person to have by your side, his enthusiasm to explore and take interest in the country around us was overwhelming.

At the Forrest River our hearts lifted when we met up with Duncan. Duncan who had been working as a fruit picker in Kununurra, waited with freshly baked bread and cakes from the camp ovens. It was great eating fresh fruit and vegetables after living off dried rations for 2 ½ months.

In only a matter of hours, Ewen and I were back on our mountain bikes heading across the Milligan Ranges to Wyndham. The 210 kilometre track via the magnificent Cockburn ranges was intersected with several muddy tidal rivers. Spurred on by the thought of crocs, our fatigued muscles had no chance of recovering on the sandy tracks that followed.

From Wyndham we were to run to Kununurra and to avoid the 36 degrees centigrade heat, we decided to run the 103 kilometres overnight. The hard bitumen forced Ewen to stop with knee problems but I carried on throughout the dark night alone, finally exhausting myself in the chilly hours of morning. With no running training for 2 ½ months my muscles were beginning to feel the strain.

Tired and wrapped in a blanket, I slumped in a chair next to my support vehicle and dunked my feet in ice water. As I dozed, I wondered why I tortured myself but before I could find the answer, I fell into a deep sleep and freed myself from the agony of aching muscles.

Awakened, by Duncan half an hour later, I forced myself on trying desperately to reach Kununurra 15 kilometres away before the heat intensified. No day was a rest day. Even in the scenic tourist town of Kununurra, the vehicle needed an oil change and check-up, a puncture, unable to be fixed by two service stations, also needed our special attention and our bikes, having crossed several salt water creeks, needed a service.

Before leaving Kununurra Major Bob Quoldling and his wife invited us for a meal. Bob was the Officer commanding the Kimberley Squadron and he had taken an exceptional interest in my expeditions over the years. I felt privileged to think that a person so highly ranked would want to meet us.

There was still a long road ahead, a 1200 kilometre cycling leg to Derby, via the Bungle Bungles, Geikie Gorge and Winjana Gorge, followed by a 222 kilometre run to Broome.

Biking with Ewen into the Bungle Bungle range along a 72 kilometre Spring Creek Road was very exciting, scenic but bone jarring. We ploughed through deep powdery bulldust that choked our chains and sprockets, flew down steep grades into washed out gullies and strained hopelessly in the soft sand. Even the experienced four wheel drivers, who could hardly beat our pace, complained about the rough track.

After exploring the labyrinth of beehive domes, delicate sandstone formations encased by a skin of silica and lichen, some 350 million years old, we left this unique and beautiful massif and headed southwest on the Great Northern highway.

Free from the jack-hammering effect of the corrugated dirt, but slowed by tyres designed for gravel, tormented by flies and 36 degree heat we sweated with saddle sores and rode up to 14 hours a day.

Our final cycling section to Derby was via a 250 kilometre corrugated track to Tunnel Creek; a limestone cave eroded by water. Nearby we also visited the fossil rich Winjana Gorge which is home to several huge fresh water crocodiles and ancient Aboriginal art and a place I had my hair cut by a hairdresser who just happened to be there.

It took Dennis and I three days to run 222 kilometres from Derby to our starting point, the historic pearling town of Broome. As we neared the end we pounded the bitumen as a local reporter leapt out of her car and clicked a couple of shots. My mind was bursting with past highs in my life so far, including six years travelling the world, a world kayaking record and five expeditions in the Kimberley. But what next? Then I thought, what about doing something similar as this trip, but around Australia? And that’s what happened the following year.

When we stopped running there were 3,500kms of the most scenic and fascinating country in the world behind us. In 91 days my English friends and I had achieved and experienced a great deal and formed a special relationship with an area still virtually untouched.

Soaking my feet in ice water opposite the post office, it was hard to believe our daunting marathon was all over, but I just knew the timeless wonder of the Kimberley would draw me back and this was the start of something bigger.