To paddle the Zuytdorp Cliffs

A Days Paddle In The Life Of A Sea Kayaker

After kayaking 600 kilometres from Perth, averaging 60kms a day we pulled in to Kalbarri after having a great days paddle along a stunning cliff line. It was in Kalbarri that we were to have a two day rest to prepare for one of the longest, wildest nights that we would ever encounter. The trip up the coast had been full of excitement, but it was the next section that we had all been longing for.

The team: Les, Tel & John leaving Perth

The Team

The Cliffs

How we got there

Reefs south of Kalbarri

Kalbarri cliffs

Our stop in Kalbarri was certainly buoyed by the hospitality of Ken Wilson, a Scotsman who lived on the hill near the river mouth over looking our route along the cliffs. He had been host to Paul Caffyn, who 20 years earlier had paddled into Kalbarri on his around Australia paddle.

Ken Wilson made us welcome

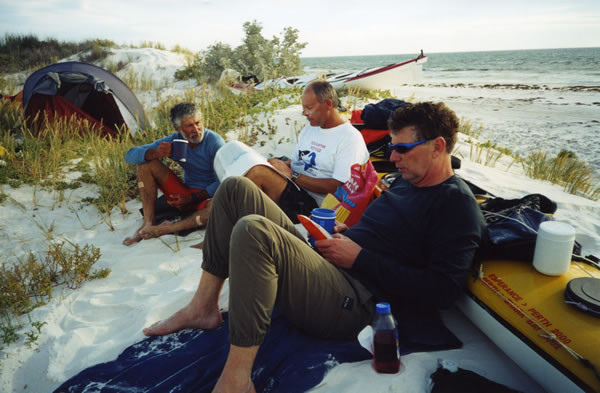

The two days was spent checking and readying gear and food. Small jobs took time, nothing could be rushed, as the final push to Steep Point was going to be very testing, physically and mentally. Tel, John and myself were heading out, Tel and I were paddling Mirage 580s and John paddling a Raider X.

It wasn’t pleasant rising at 4.00am, as we all felt deprived of sleep, but we knew that it was important to get on the move. We had a big day ahead of us. Our goal was to paddle a 170 km stretch of coast, lined by cliffs, and without landing. A little daunting, but I just took it as another challenge. I didn’t know how the others were feeling and I didn’t ask. We dealt with our challenges in different ways, so I just focused on the job ahead.

It was still dark when we left Ken’s home and walked down to the beach to the sound of bagpipes. Ken used to play the bagpipes, but now he has Hamish, a life size dummy that stands next to his house and plays a tune when a passing person triggers the sensor. It’s become another tourist attraction in Kalbarri.

By 5.45am, just as the first rays of light allowed us to see, we were ready to leave. Cheered on by Marian, Les and Ken, we moved out of the river mouth followed by a fishing boat. Before us were kilometres and kilometres of sand cliffs as far as the eye could see. We chatted as we left but fell silent for a while, each of us simmering over our own thoughts. I eventually broke the silence and started singing. Tel and I had attempted to sing all the songs that we knew on our journey up. We were surprised how many 60s & 70s songs we could remember, well the first few lines at least. To our surprise John, who has been very quiet during the trip, suddenly broke out with a rendition of the 6.00am time clock and a song, ‘It’s a beautiful day’. We were silent again. Occasionally the silence was broken with a triviality. It’s amazing how many times the wind and weather conditions can be discussed.

It seemed strange that we didn’t have Les paddling ahead, but the long hard days on the way up had injured his wrist. Just before Kalbarri, Les had started to suffer with a serious tendonitis problem in his right wrist and he knew then, that only a long rest would help its recovery. This was a mighty blow that none of our team expected to happen. Les was the strongest paddler, and although Tel initiated the trip, Les had been the driving force in getting the expedition on the road. It was probably one of the most disappointing moments of Les’s life. One year of planning, one year of focusing on a challenge only attempted once before by the legendary Paul Caffyn 20 years ago, was now in tatters.

Now, as Les tends to his creaking wrist, and joins Marion as our support crew, the team of three, Tel Williams, John Di Nucci and myself, launch ourselves on a paddle that we will never forget. The challenge of paddling the Zuytdorp Cliffs was now reality.

Four fishing boats were scattered across the ocean ahead of us. They had already been working for several hours. On land a group of fishermen with 4 wheel quad bikes, stood casting their lines from the beach. Waves pounded a rock ledge, then spilled up the beach. Behind the fishermen stood a high sand ridge, which was to be part of the coastline for the next 45 kms.

Along the first part of the cliffs, mostly sand with rock outcrops and rock ledges

Large groups of goats roamed along the shore and became a common sight. The beaches were littered with their tracks. On a previous trip I had walked the cliffs and at the time I’d noted the erosion damage they’re done to the area. Apparently the goats are now being harvested and fetching $40.00 a head.

A number of flying fish suddenly became airborne in front of us, shining like silver and seemingly gliding forever. One leaped out near John, glided in front of me and narrowly missed the back of Tel’s head. It was a spectacular show, one that we had seen many times before, but it made us aware that a unique brush with nature could easily turn out in disaster, if we were hit by one in the night. I could just see the headlines: Paddler slapped in the face and is knocked out by a wet flying fish.

Our relationship with the sea was uplifting. There was always something around us, whether it was a creature in the sea or the beautiful scenery on land. It inspired us to keep paddling. Today was no exception. As we paddled with the rhythm of the swell, I heard a familiar splash behind me. I instantly thought it was a shark following as I’d had similar experiences before, whilst paddling the Kimberley coast. I turned to see a dark shape at my stern. I shouted to John to check behind me. He stopped paddling to let me catch up, and shouted back that there were two sharks following. As soon as I had passed him the sharks disappeared, at least for the time being.

On the journey up, while having lunch on the beach at Port Gregory, a fisherman struggled with a pretty hefty shark. Within 30 minutes of hooking it, just about the entire population of Port Gregory was looking on. Apparently a shark had been taking off with fishermen’s tackle all week. Some two hours later the shark was hauled into the shallows, gaffed and pulled up on to the beach with the locals rejoicing. It was a tiger shark about three metres long.

Also on the paddle up, Tel and Les had been practising what they called the Zuytdorp break. They would jump out of their boats and relax in the water for a short time and then jump back in. The idea was to stretch, and give themselves a new lease of life whilst paddling the long journey along the Zuytdorp cliffs. The idea had merit in certain situations and weather conditions, but with the presence of sharks and with the rough conditions that developed after midday, these plans were put on hold.

The cliffs start to get bigger

Every hour we stopped for a few moments, had a drink, a bite to eat and a very short rest. Tel and John would take the opportunity to have a jimmy-riddle. They had to go just about every hour. Did they have a bladder problem or what? They took off their spray cover, strategically positioned a container to catch the fluid and then emptied it overboard, rinsed the container, breathed a sigh of relief and placed the cover back on. The task became a little more difficult as the sea deteriorated, but they still had to do it.

The weather gets a little more wild the further we travel

A photo opportunity

It was important to keep our fluid and food intake up. John and I only drank water, but Tel liked gatorade. To keep me going through the night I cooked up my favourite marathon food – rice pudding. I find it an excellent food to keep my energy levels up. It tastes good, digests well and is a carbohydrate, a good food source to keep my body working overtime. Between the portions of rice pudding, I ate my usual; nuts, raisins, dried fruit, and breakfast bars. For a special treat I took along two Snickers bars, I had one for breakfast, and gave the other to Tel, who at the time needed an energy boost.

A check of my GME Etrex GPS indicated that we were travelling at 7kms an hour. It was a good speed if we could keep it up. I was quite impressed with how rapid the GPS located the satellites and was ready to go. It was important to get a reading quickly, so I didn’t have to sit floundering in rough conditions. With the featureless coastline the GPS was ideal for indicating the distance we had travelled.

By 1.30pm we reached the first part of the continuous cliff line. By this time the wind was howling and waves were crashing into the cliffs. Around the 60 km mark I took another GPS reading to establish the position of the Zuytdorp wreck site. We didn’t want to miss it. The wreck sits underwater close to the cliffs. I had thoughts of peering at it through my divers mask, but unlike the previous day the sea was too rough. Unfortunately when we located the site all we could do was to take a few photos and be happy with just being there. I had visited the wreck site on a previous walk, so I was able to recognise it.

The Zuytdorp ship was bound for Batavia (Jakarta), sailing from Holland. The 45 metre, 40-gun Dutch merchant ship sailed into the 60 metre cliff in 1712 with 250 passengers and crew and a cargo of 248,000 guilders in newly minted coins. The wreck was found in 1927 and first explored by divers in 1964.

Close to the Zuytdorp wreck site

At 3.00pm we left the wreck site, turned north-west again following the cliffs as far as the eye could see. Then about ten kilometres further along the coast the vertical cliffs eased and were replaced by an extraordinary rock/sand cliff line that furnished an array of shallow caves weathered and eroded by the wind and rain. There was a beach beneath them, although it looked impossible to land, due to the rocky reef. It was a fascinating part of the coast. Stalactites and crazy sandstone patterns and sculptures with magical appearances formed inside the caves. It was a unique area to explore and a mystical part of the coast. I looked on with great curiosity. I wondered what it would be like standing closer and peering into these huge archways and shallow caves. My imagination ran wild as the weathered cliff line succumbed to the varying rock sculptures and cave in’s. Several deep gullies intersected the cliffs forming beautiful hideaways and routes up onto the cliff tops. Vegetation was also lush here.

The vertical cliff faces returned. It had been a beautiful and interesting section where the intriguing formations allowed my imagination to wander. We were pitting our skills against the elements, but I found it so relaxing and rewarding to be able to study an incredible cliff line, that so few people have seen.

At 6.30pm it was time to make a radio schedule with Les. I delayed doing it for half an hour in the hope the sea would calm. It didn’t. It was too rough to chance taking the satellite phone out of my day hatch without support, so I got Tel to come alongside to steady me. When I got through, I told Les that despite it being rough, we were going well, and had paddled 82 kms, which was nearly halfway.

Rafting up to rest for a few moments

The swell getting bigger

At this point we took the opportunity to attach cylume light sticks, strobe lights and torches to our heads. This proved to be a difficult task in the rough conditions. As we moved off again the sun was setting on the horizon, but we gave it little attention. Normally we would have been oohing and aahing and saying how beautiful it was, how lucky we are, and isn’t it great to be out here in the wild. Tonight we were really in the wild but somehow the sunset wasn’t our main focus. We were now halfway, so the closest safe heaven was 85 kms away. The cliffs prevented us from landing before then. Within two hours we would be passing Womerangee Hill (287m), and the highest point of the cliff line (260m), but unfortunately by then it would be dark and we would only be able to see the cliff outline in the moonlight.

By 8.00pm, and 14 hours into our paddle, Tel, who had had trouble keeping awake all afternoon was getting worse. He hadn’t slept the previous night. His strategy was to raft up with John and have a quick nap, in the hope that he could revive himself. A few minutes later he would be off again. Unfortunately the naps had little effect so stops became a regular occurrence throughout the night. I drifted close by keeping an eye on their lights and the longer that Tel rested the colder we all became. It was always a relief when we started paddling again.

Tel led the way, while John and I paddled each side of him watching every movement that he made. We had kept a tight formation all day, but it was now even tighter. It was extremely important not to become separated.

Every time a large following wave would pick me up I would spear my boat over to the left to ensure that I didn’t collide with Tel. He mostly surfed them straight, as he was at the mercy of the wave and too sleepy to fight them. Concentration for all of us was at the max.

Lights from two fishing boats several kilometres apart, got closer. They were anchored up for the night and although their lights were on, I saw no life on board. I wondered if Tel would be tempted to divert towards them, but we passed them by. The way ahead was now completely dark. The cliffs loomed over to our right. We estimated the swell being about three metres and the wind being around 30 knots. The conditions were certainly testing our skills.

About 10.00pm Tel suddenly came out of his trance and declared that he was over his sleeplessness. “Lets go” he said, “I feel great”.

For the next hour we paddled with gusto. Life had returned to the old dog. We again flew up the coastline surfing some waves and being crashed upon by others. It was great, we were having the time of our life, scooting down waves and feeling a sense of achievement as we headed towards the moon. Then Tel suddenly fell back into a hole, this time a bigger one, and he was forced to take longer cat naps.

Meanwhile the sea seemed to deteriorate further with rogue waves breaking heavily and increasing our vulnerability. The strain of peering into the darkness, being prepared for a wave to dump on us, and having to concentrate heavily on our own and each others paddling was quite an effort. We were hoping that the sea would calm by midnight. It had done so virtually every night since the start of our journey. We waited with baited breath, but it never eased.

At one of our stops I paddled over to John and Tel who were rafted up. They sea was noisy as it had been since midday. I could hear waves crashing off the peaks of large swells from afar. Being surrounded by them, we all knew it was only a short time before the next one crashed over us. It was a little like playing Russian roulette. The wave may miss two of us, but crash onto the other, only metres away. I said a few words to the guys and started to move off. Then out of the darkness came a huge white breaking wave crashing down on me. As it smothered me I instinctively leant into the wave, braced with my paddle for dear life and relied on my balance to ride it out. Having little reference as to where I was, I could do little but allow the wave to push me sideways to where-ever it dissipated. It bounced me further than any other wave had taken me that day. It was like being swept away by a beach break. When it rolled on by I was wet, cold but very lucky. I used my instincts and skills to survive that wave, but there seemed no end to them. The night was far from over. With the drama continually soaring, so did the excitement and my confidence. I still felt in control and if I could keep awake I knew that I could get through the night.

We moved on again. Tel put another cylume glow stick on his head, so we could see him more clearly from the back. John and I continued to shadow Tel’s every move, by keeping in a very tight formation. We were at the most vulnerable time of the night, but John and I work well. I could see him regularly checking my whereabouts, as I did of him. It felt great working as a close knit team intent on succeeding in our quest to get through a difficult night. I have paddled and worked with John in whitewater many times before, but this was the first time that we have been on sea kayak expedition together. But that didn’t matter, I knew from the onset that he could always be relied on.

John is a wiry character, he is even smaller than me. But his size doesn’t reflect his strength and determination. In the rapids I have found few people that can be more relied upon to rescue someone in trouble. When a paddler is in a difficult or dangerous situation John will do everything to help the paddler in distress. Somehow he is able to place his small-framed body in the thick of it. He is not afraid to leave his craft to get to the accident scene, and can lift heavy boats to free paddlers from danger. Tonight John had a different role – to help a very close and tired friend to get through the night.

Tel took off again towards the setting moon and in a more westerly direction. He seemed to be in a trance and the moon was drawing him in. I shouted at him to stay a little to the right of it, so we didn’t detour too far out to sea and paddle extra kilometres. Although I knew that we couldn’t land and the cliffs were extremely dangerous, it was comforting to know that they were close by.

I had some idea of what Tel was going through, having experienced sleep deprivation on other expeditions. It’s an agonising and frustrating feeling and no matter how hard you try to keep awake it’s virtually impossible to succeed.

On some of my trips when tiredness has overcome me I have purposely encouraged myself to grab a few moments sleep. It’s like putting yourself in a trance. On the river or on a calm ocean it’s not dangerous to nod off, but the conditions that Tel was experiencing were much more dramatic. Surprisingly when you are in this trance, your body’s reflexes somehow react and warn you that you are about to capsize. When this happens, you find yourself doing an automatic support stroke. It’s quite bizarre, but I have never capsized whilst in this state.

Tel was certainly experiences an extreme case, and it is hard to believe that although he had virtually no control of his paddling and surfing, he didn’t capsize. He always seemed to drop his paddle across his deck and support himself at the crucial time.

Tel has done many exciting things in his life especially in his younger days in South Africa. He’d told us about many of his experiences as we’d paddled up the coast line. But today all he could say was, “this is the worst experience of his life”. Even the South African army days, which, he said, were pretty tough and atrocious, had nothing on this experience.

In the meantime our ground crew, Les, Marian, Carolyn and Gary, who were camped at False Entrance, found it difficult to sleep. Apart from their tents being battered all through the night by the strong winds, they were really worried about us. Les knew only too well how uncomfortable the conditions were out on the water. It was a tense night for everyone.

By 1.45am the moon, which was lost behind the clouds for long periods of time, was getting lower in the sky. Tel shouted to us that he could no longer go on. “I’ve had it”, he said. He rafted up with John and I moved carefully across to them to work out what to do. At this stage I think we all agreed that we were in a tricky situation, but we were in no serious danger. All we had to do was raft up and wait for daylight.

We had at least another 10 hours left of our journey. Our situation could worsen but I was pretty confident we could ride it out. I was feeling pretty fresh and alert despite what we were going through. John also seemed to be coping well, although I didn’t really know his true state of mind.

I floated alone for a while, watching the moon steadily fall behind a small mountain range of clouds. The light dimmed. Apart from our little dilemma, it was a beautiful sight. One to remember. How many people would have experienced such a spectacle? Our situation seemed less serious when we were moving despite being at the mercy of the wind and waves. Unfortunately it was difficult to generate body heat and it was harder to stay awake and focused.

My body soon started to cool and I needed to put on my polartec jacket for warmth, but the conditions prevented me from trying. Eventually I paddled across to John and Tel to join the raft and increase my stability. The task proved difficult. Trying to dress with the boats rising and falling proved to be too much for my stomach. I started to feel nauseous, so I immediately pulled away from the raft dry retching, but luckily my stomach soon settled and I was able to conjure up another plan to get my jacket on. Before leaving for the trip I had fixed an outrigger system on my kayak, so in times like these I could attach two small pontoons, one each side of the boat, to give me more stability. I quickly attached the pontoons and I was able to take my PFD off and put my warm jacket on, without feeling threatened of capsizing. I was extremely pleased with the system but even happier to be warm. The extra stability from the pontoons helped me to keep afloat. I worried less about falling asleep and rolling over, however I couldn’t become too complacent as the breaking waves continuously threatened.

I sat quite comfortably in my boat, thinking and watching the moon fall gracefully behind a mass of clouds. I was quite content and relaxed despite the elements running hostile. Just as I was feeling on top of the world, the moon slid below the horizon, plummeting us into total darkness. Even the faint outline of the tall cliffs was now gone and we had entered the second phase of night.

Feeling threatened by the thought of drifting into the cliffs, John and Tel started paddling out to sea while still rafted together and stopped when they thought it was safe. I constantly monitored their lights and every so often I would go over and talk to them. For the second time, when next to their rising and falling boats, I felt nauseous. This time I vomited a little, but I soon felt good again. It was a relief not to become sea sick. I have only experienced sea sickness four times in twenty-four years of sea kayaking, but it was very debilitating.

Time passed slowly and again and again I was swept away by large waves. I could also see John and Tel being dumped upon. It became difficult and draining sitting in the boat at the mercy of the sea. I had thoughts of rafting up with the guys, but I thought it could create more difficulties in these conditions, as the three boats side by side would continue to bump into each other.

I floated by myself until 4.25am, but the strain of having to be alert and awake was starting to tell. It was time to join the others. Once rafted it was like being in heaven. However, the boats continually crashed together, which soon became a concern, as permanent damage could occur. But at that point I wasn’t too concerned, I was happy to be able to hold on to another boat, and rest my eyes, even if was for a very short time. My taste of heaven was brief though, as a big wave came through and dragged us apart. We clawed our boats back together and hung on, waiting and hoping that the next one would be less powerful.

Periodically through my relaxed state, I would hear John enquire whether the cliffs were close. Robotically, I would force myself to look up fleetingly, see nothing, say no and rest my eyes again. In reality it was too dark to see any thing anyway, so we’ll never know how close we really were. Our boats continued to bang together as we were lifted and dropped by every wave. Relief finally arrived when daylight approached and Tel tried to paddle again. At that point I instantly came alive.

I peeled away from the raft first. Tel followed and within seconds I heard John shout. I looked behind to find him capsized 20 metres away and out of his boat. There was no time to be lost, so I paddled backwards quickly to John’s boat. When I arrived John was on the up wind side of his boat trying desperately to swim towards it. He was only 2 – 3 metres away, yet despite his desperate attempt to catch it, the wind drifted us apart. I will never forget the anguish on John’s face as he held on to his paddle with one hand and swam with the other. I had three choices; I could let his boat go and paddle around to him and then tow him back to his boat, or I could tow his boat to him, or I could just lean across his boat and perform a solid draw stroke to stop the boats from drifting. I chose the draw stroke option because it was the quickest, safest and most efficient way to get to him. As soon as my draw stroke took effect, John came closer and when he was within a paddle length, I held it out and pulled him in. In less than a minute of arriving next to John’s kayak, he was safely back inside.

As John bailed out the water he said, “I owe you one”. It was a funny thing to hear from John, who over his paddling career has saved many paddlers from danger. We were a team, and helping each other was part of being there. John had helped Tel to get through the night and I had helped John. To me the incident wasn’t a big deal, we had the skills and experience to nip it in the bud. John had been leaning across Tel’s boat for 3 hours and as soon as the raft broke up, his balance was effected and over he went. As soon as he turned the kayak over, he lost his grip on the boat and it blew away from him. He couldn’t have picked a more dramatic place for it to happen.

The cliffs 300 – 400 metres away were glowing with a hazy redness. They were tall, steep and cleaned edged like a slab of butter. They were a magnificent sight that we were unable to appreciate at that particular time. The morning brought relief. We knew now that our goal was in sight. It was a case of taking care and to slowly keeping moving towards our goal, preferably in the upright position. At this point I felt the challenge was over. For Tel though, it was still very demanding. We made a satellite call to our support crew and they were relieved that we had survived the night, but very worried when I mentioned Tel’s difficulties.

When I checked my GPS we were surprised that we only had 30 kilometres left to paddle. We must have drifted over 10 kilometres in the night, which was a bonus. In reality the 30 kilometres to safety should have taken 4 hours 20 mins but it took 6 hours 30 mins. Tel was still very tired in more ways than one and he tried whatever methods he could muster to keep awake. He splashed his face, chewed on his hat, sang, talked to himself, talked to us and nibbled on a carrot. None of these were really effective, although talking to us did seem to help the most. The problem was, we had nearly exhausted the content of our conversations over the last two weeks and chit-chat was becoming more difficult.

Cliffs near Dulverton Bay (False Entrance)

When False Entrance came in sight, and although it was still over 10kms away, we felt as if we were home. Tel struggled on, with John leading us to the entrance. I paddled beside and behind Tel who continued to be angry and frustrated with himself as he nodded off and couldn’t do a thing about it.

Specs on the cliffs drew closer. Fishermen cast their lines and our crew waved and took photos, although they were hard to spot. We too were only specs in the ocean.

Throughout our ordeal, the team was very close. From the very start that morning we were as one. If someone fell back for any reason, we all stopped. On the hour we stopped for a few moments to drink, to eat or have a pee. We had established a boundary and every one kept within it. We respected each others talents and formed a bond. But John and Tel, who had been close friends for several years, were now going to have a bond that would be even stronger than before.

As we paddled into False Entrance (Dulverton Bay) against the howling wind, I felt proud of what we had achieved, we were all safe and Tel could now sleep forever and reflect on his ordeal. We had learnt more about ourselves, about our friends and about sea kayaking since starting our journey from Perth.

Arrived at False Entrance. On shore after over 30 hours in the kayaks

False Entrance on a good day

With a southerly wind blowing, the surf at Dulverton Bay was pretty flat. Normally, when there is a westerly or north-westerly wind, there is a huge surf in the bay. We had been concerned about landing here and had thoughts that we might have to continue further to Steep Point, but that worry was no longer necessary. A reef fronted the beach but we were able to paddle across it. As we moved over the reef our support team stopped taking photos and waded in the water in a desperate attempt to help us out of our boats. Marian’s camera, which was on a tripod fell over, she then waded in the water and stubbled up to her waist in her nice dry clothes. I was wondering what all the fuss was about. We had always landed without help. Unbeknown to us, they had been very concerned about our condition, especially Tel’s, so they were ensuring we had help.

To my surprise I wasn’t even sore. I felt better now than I did on the first hour of the journey and I knew that I could paddle on well beyond nightfall. I had no chaffing marks and no blisters and I was full of confidence knowing that I could do something even bigger.

As for Tel, he was in big need of a sleep. John, well he didn’t look too fresh at the time of our landing and he did say later, that he had needed the next day to rest to feel 100% again.

Strong wind continued for the rest of Friday and increased further to over 30 knots the following day (Saturday), so we had no alternative but to take the day off and rest, play beach golf and write our diaries.

Just when we thought the blustery weather had set in, it calmed enough on Sunday to allow us to start paddling again and finish what we came here to do – paddle on to Steep Point. We left camp at Dulverton with a south-easterly wind blowing. Having to paddle 34 kilometres of cliff line seemed an easy task compared with what we had been through. We were very relaxed and were able to appreciate the scenery, which was some of the best you’ll see in Australia. The swells had dropped, but the rebound from the cliffs was quite savage, compared with the easier swell and wind conditions. Tel and I continued to sing, but not with the same enthusiasm as before. Our thoughts were elsewhere. When we saw the Steep Point cliffs it felt as if the dream was complete. Nothing short of an unprecedented incident would now stop us from finishing.

Coloured balloons used by fishermen at the point were bobbing on and out of the water. Although we wanted to paddle close to the cliff, the fishing lines were a hazard we didn’t want to tackle. This was one of Australia’s premier fishing sites. Big fish are caught here and I expect that big sharks were roaming under the water, so it was a big incentive not to capsize. John waved to the fishermen, but we saw no response, probably too engrossed in catching something big.

Tel & John rounding Steep Point

Meanwhile as we enjoyed drifting into South Passage of Shark Bay, Marian and Les were having a terrible time. When they tried starting the car the battery was flat, so was the spare. Then to make things worse the immobiliser wouldn’t allow the car to be started with jump leads, so Les had to cut the leads to take the immobiliser out, and then join them together again so as to by pass it. To make things even more frustrating the track into Steep Point was pretty rough and they had trouble climbing two or three of the sand ridges. So by the time we met them on a beach about three kilometres from Steep Point they were not in a mood for celebrating.

John & I

In the shelter of Shark Bay and time to go home

We quickly unloaded our boats, tied them on the trailer and tried desperately to fit all the gear into the vehicle. Within 40 minutes we were driving out on the rough track, and secretly praying for everything to go right on the way home. It was Marian’s four wheel drive, so we felt guilty about it being knocked around. On the way home, the car had to be stopped twice and both times the battery failed. We then had to jump lead it. Celebrations that day were put on hold. We focused on getting home.

Homeward bound

Now I have walked the cliffs and I have paddled them